|

There

are several ways to capture infrared images. In the film days one had

to buy infrared sensitive film and use a special infrared filter in

front of the lens. Modern digital cameras are specifically

designed not to

capture infrared light and have therefore a special infrared cutout

filter installed in front of the imaging sensor that filters out most

of the infrared light. Some cameras have weaker filters than others and

can capture infrared light with a infrared filter in front of the lens.

The negative side of this method is that the shutter has to be open for

long periods of time, hence requiring a tripod. In

order to use the camera for IR photography and using regular shutter

speeds, the camera's hardware has to be modified. This modification is

not for the faint of heart and shouldn't be attempted by inexperienced

people that never handled electronics before. There is a serious risk

that you will damage your camera beyond repair. There is also a risk

for serious electric shock as many cameras have a big capacitor (330

Volts!) for the flash built in, that holds its charge for a long time.

If you have even the slightest doubts of what you are doing, please

take my advice and send your camera to one of the professional

conversion services available. Two of those services are www.lifepixel.com and www.kolarivision.com Those

two vendors are also selling special infrared filters for DYI projects.

I chose the filter from Kolari as it was half price. The camera I had

for the conversion is a Nikon D70 that I picked up for $50 from a local

classifieds website. The D70 is an excellent donor for an IR project.

It's a good camera with 6 Megapixels and a large image sensor. DSLRs

are much better suited for IR photography as post processing the images

require more dynamic range which compact cameras can't deliver as

well. the following is a little writeup about the conversion. Please note that this procedure will definately void the camera's warranty.

|

This is the Nikon D70 camera ready for the infrared conversion. It's

extremely important to have a clean workspace and the right tools. You

have to have a ground strap (useful for all electronic projects) and a

good set of precision screwdrivers.

The little black

square you see next to the camera is the infrared filter. I chose a

filter that is sensitive to a wavelength of 720nm. |

|

|

Next step is to take the bottom plate off. There are three different

screw sizes for the bottom plate alone, so it's important to note what

screw goes where. As with any project it's extremely usefull to take

photos along the way, so you can see what you have done.

|

|

|

This photo shows the bottom plate off. Sorry, the photo is a bit out of

focus. Now one has to disconnect the two flex cables in the middle and

on the right of the image. Those connectors are rather small, so one

has to be careful not to damage them. If the connectors are damaged,

it's game over.

|

|

|

After the bottom plate is off, one can remove four screws, two on the

left and two on the right side of the camera. Now the back plate that

holds the LCD screen in place comes off the camera and reveals the CCD

sensor board. This sensor board we need to get to in order to replace

the infrared filter.

|

|

|

With the CCD sensor board

removed you can see the camera's shutter assembly. This is a good time

to inspect the shutterblades for wear and tear and especially for oil

residue on the blades. If you can see oil on the blades, it's not worth

doing the conversion as it would require an overhaul of the shutter. If

everything looks ok, you can go ahead and modify the sensor assembly as

shown in the next steps.

|

|

|

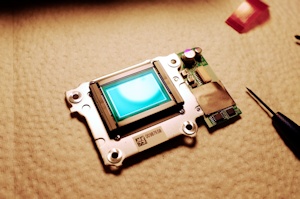

Here you see the CCD Sensor assembly board. The blueish tint on top of

the sensor is the factory infrared cut filter that needs to be removed

and replaced with the infrared filter. The filter is held in place by

four tiny screws. This replacement is actually straight forward. The

only difficulty is to keep the sensor itself free of dust. The way to

do this is a to work fast, work with latex gloves and have a little

airblower handy in case some dust settles on the sensor while working.

Since I had to work fast here, I had no time to take a photo of the

filter removed.

|

|

|

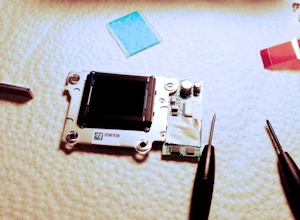

And

here you see the CCD sensor board with the new infrared filter in

place. The filter is really dark. The light blue square on top of the

board is the factory infrared cut filter. It's important not to scratch

or touch this filter in case you want to reverse the conversion at a

later date. The rest of the conversion is a reversal of the steps

above. The most tricky part of the whole process was the fitting of the

tiny flex cables.

|

|

It

is important to note that infrared photography shifts the focus of the

camera. On cameras with autofocus the focus has to be re-adjusted,

which is - again - nothing for the faint of heart as it requires

precision tools and experience where the focus needs to be at. The best

way of going about it is to calibrate the focus to one specific lens.

This lens should be suited for infrared photography. Some lenses have

coatings that are not suited for IR and can produce hot-spots,

basically bright flares, that can ruin your images. A list of suitable

lenses you can find here: http://www.kolarivision.com/lenshotspot.html

Every

camera has to be calibrated differently, in case of the Nikon D70

calibration is relatively painless as the autofocus adjustment screws

are located inside the mirrorbox and can be accessed without taking the

camera apart. Older lenses have a infrared focus shift indicator on the

focus scale (usually a tiny red dot) which is helpful if you don't want

to touch your camera's autofocus system. Taking photos in infrared To take photos in the infrared wavelength requires a bit of re-thinking

as digital cameras are not designed to shoot in infrared. You have to

learn how to control your white balance with custom presets as the

camera has no way to compensate for infrared. Without custom white

balance, an image would look something like this:

Certainly

not very pleasing. Now the easiest way to get around this problem is to

convert the image to Black and White, using image editing software.

This way you will end up with something like this:

Now

this doesn't look all that different compared to a regular Black and

White image, except for the grass and the foliage on the trees that

appear white. In an infrared image, everything that emitts or reflects

infrared appears brighter, while subjects that reflect low amounts of

infrared appears darker. As I said before, the camera's auto white

balance will no longer work, so in order to get color photographs, we

have to set a custom white balance with the help of a grey card. The

idea behind a grey card is that you can tell the camera what is a

certain shade of grey (in the photography world this shade is 18%

grey). Once this is established, the camera "knows" what grey is and

can set all the other colors accordingly. After properly setting the

white balance, a unadjusted color infrared photo straight out of the

camera will look something like this:

Although

this is already better then the initial image without the proper white

balance, it still is a bit boring. There is not a lot of contrast and

the image looks a bit flat and dull. While the color of the sky would

be ok for the planet Mars, it would be a lot better if we could achieve

a more Earthly color. That's were image editing comes in.

In programs like Photoshop, Paintshop Pro or The Gimp, you can

chose the Channel Mixer to change that. You basically have to swap the

red and blue channels and boost the contrast a bit. After that you

might end up with this:

Now

that looks a lot more natural. Of course the infrared makes the grass

look white and other detail in colors we are not used to, but we are

not trying to achieve an all natural look. We have to remember that we

are taking photos in a wavelength normally invisible to the human eye. Over time I will expand this section with Archaeological samples as well. Stay tuned.

|